In Translation

How Translated Works Make me a better writer

As a reader, I’m drawn to works in translation — novels that don’t start their life in English but find their way to my heart, nonetheless. But can reading translated works make me a better writer in my own native tongue?

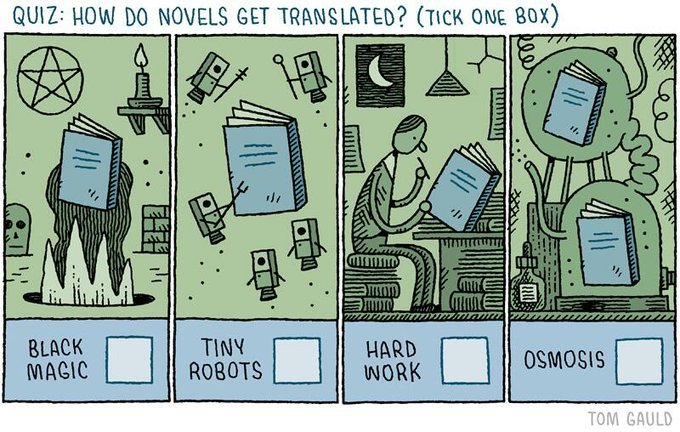

Cartoonist Tom Gauld on X: "'How do novels get translated' (my cartoon for Saturday's @guardianreview): https://x.com/tomgauld/status/445487412966203392

NOTE: Herein, translated works and works in translation refer to literary novels that have been translated into English.

“Translation is entirely mysterious. Increasingly I have felt that the art of writing is itself translating, or more like translating than it is like anything else.”

Translated Works

Most of my favourite novels are translated works. Haruki Murakami’s 1Q84, Marina Yuszczuk’s Thirst, Édouard Louis’s History of Violence, and Hila Blum’s How to Love Your Daughter are a few. Much of contemporary English-language fiction feels the same to me — formulaic, designed less as art and more like a pitch for a Netflix series. The novelist Lance Olson addresses this in his essay “Renewing the Difficult Imagination.” He writes: “The problem isn’t simply that people are reading less. It is also that they are reading easier, more naively.” Regardless of genre, he argues, the typical bestseller usually delivers a neatly packaged story in easily digestible morsels: clear heroes, clear villains, and a comforting linear journey from beginning to end — conflict, climax, resolution, and done.

Consider translated works. They often resist contemporary English-language storytelling norms, favoring complexity over straightforward, hero-driven plots. Japanese author Haruki Murakami’s novels, for example, meander through psychological mazes and surreal landscapes, using indirect, implied characterization. In Portuguese author José Saramago’s Blindness, there are no clear heroes, only morally ambiguous characters whose motivations are murky. French author Édouard Louis combines fiction and lived experience to explore broader societal issues. Or, as is the case with Sjón’s Moonstone: The Boy Who Never Was, a novel deeply rooted in Icelandic culture, translated works might reflect cultural, historical, or political conditions that are specific to the author’s region but resonate with universal human concerns. But because I don’t read these novels in their original languages, what inspires me isn’t simply their stories, but how the stories are told — which arrives through translation.

There’s an additional layer to this: I also read a lot of works in English by authors for whom English is a second — or even third, or fourth — language. This includes the novelist Yelena Moskovich. I believe Moskovich’s experience with myriad of languages makes her more attuned to nuance, more daring in her choices — and I’m not alone.

“Moskovich’s mother tongue is Ukrainian, and while her English is faultless, there’s a pleasing otherness about her syntax and word choice, a sense that there are different languages operating just beneath the surface of the text.”

— Alex Preston, reviewing Moskovich’s Virtuoso for The Guardian, 2019

Background

When I was sixteen, I participated in a student exchange program. I left my small rural town in Virginia and boarded a flight destined for Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. I couldn’t have been more excited. Rio — renowned for its picturesque beaches, an iconic Christ the Redeemer statue, and a legendary Carnival street festival — was a sprawling city with over nine million inhabitants. My hometown, on the other hand, with its population of eight hundred, had a grocery store, a gas station, and an annual Fourth of July parade, where members of the volunteer fire department ambled down Main Street, tossing pieces of candy. I was a caged bird finally set free.

I’d prepared for my exchange as best I could, paying attention in my tenth-grade Spanish language class like my life depended on it. Then mid-flight, a passenger kindly informed me that Spanish wouldn’t do — Portuguese, darling, was Brazil’s official language! And oh, Portuguese … it was a hard language, guttural and nasally. Its vowels and consonants felt like marbles lodged in the back of my mouth. But learn it I did, or at least enough to get by. Still, there was one word I kept hearing in songs on the radio that I didn’t understand: saudade. When I asked a classmate to translate it, she said that was impossible. Saudade didn’t have an English equivalent.

“It's like being homesick for someone or something,” she said, “but more than that.”

Missing, longing, melancholy, nostalgia … these words came close, but saudade’s true meaning remained elusive. So, there it was: an entire emotional state that I couldn’t experience, at least not in the same way Portuguese-speakers could, because my language didn’t have a word

for it.

This idea floored me — and the art of translation has fascinated me since.

An aside on saudade

The Dicionário Houaiss da Língua Portuguesa defines saudade as a “somewhat melancholic feeling of incompleteness … related to thinking back on situations of privation due to the absence of someone or something, to move away from a place or thing, or to the absence of a set of particular and desirable experiences and pleasures once lived."

A better definition comes from A. F. Bell’s In Portugal, published more than 100 years ago in 1912. According to Bell, saudade is “a vague and constant desire for something that does not and probably cannot exist, for something other than the present.”

Isn’t that gorgeous?

How Translation Works

As you might suspect, translation is more than simply swapping one word for another. It’s about choosing how to convey tone, rhythm, and emotion in a way that feels true to the original work while resonating with the new language’s readers. It’s intuitive, deeply creative, and filled with choices that go beyond the text’s literal meaning — a precarious dance between faithfulness and creativity. Gazelle Mba, a Nigerian writer in London writing for The International Booker Prize, elaborates:

“Every text contains within itself the possibility of its translation. When we pick up a book by an author writing in our native language, there is a tendency to think of the work as definitive and closed. But when we read in translation it reveals to us an alternative vision of that work formed from an entirely distinct linguistic system. Language is never static, a book can always be otherwise.”

Speaking with Mba, translator Polly Barton emphasized the importance of capturing the original work’s tone. She explained that it's not just about literal accuracy but about delivering the right emotional equivalent to a new audience. “[S]ometimes taking the longer route — veering away from the translation that seems, prima facie, the most ‘faithful’ — actually takes you closest to the voice, the tone, the spirit.”

Translator Daniel Hahn told Mba that even something as small as how a character says hello can carry dozens of choices, each one imbued with layers of meaning:

“There is almost nothing that doesn’t have a choice involved, which might be an aesthetic choice, or it might be an ethical choice, about what precisely you are choosing to represent, about the character, about the text, and you’re not necessarily making all of those choices deliberately or consciously.”

Race and ethnicity, gender identity, economic and educational status, personal values, politics, religious beliefs, and on and on. Certainly, these influence translation choices. So, it feels safe to say that translation inevitably involves interpretation of a sort.

The Iliad

To demonstrate how different translators’ interpretations can vary, let’s look at Homer’s epic poem The Iliad—more specifically, its first words (Homer, Iliad, 1.1):

μῆνιν ἄειδε θεὰ Πηληϊάδεω Ἀχιλῆος ...

An actual word-for-word translation, according to Sam Jordison, writing on this very subject for The Guardian, would be something like:

“Wrath sing goddess of the son of Peleus of Achilles …”

In English, imperatives usually fall at the start of a sentence, as in “Put down that donut, Leith, it’s mine!” And this is how the folks at Open University handled translating Homer’s Greek — with a straightforward, English-language approach:

“Sing, goddess, of the anger of Achilles, son of Peilias …”

But Ancient Greek language word order is unique:

“Greek word order, as a non-configurational language, is driven by information structure in more dramatic ways than configurational languages like English … Because of the non-configurational nature of Greek, looking for the proper order of Verb, Subject, and Object is already starting off on the wrong foot.”

— Mike Aubrey, Koine-Greek.com

Put in plain language, Ancient Greek and English handle sentence structure differently. In English, we depend on fixed word orders — usually Subject-Verb-Object (SVO) or Verb-Subject-Object (VSO) — to avoid confusion. For example, in this sentence "Leith eats donuts," the SVO structure clearly tells us who is doing what to what. (Yum!)

Ancient Greek, however, is more flexible. Grammatical roles, like subject or object, are indicated by a word’s inflectional ending — not word order. (If you’d like to dive further into Ancient Greek language verb structure, inflection, and translation, check out Ancient Greek for Everyone on the Pressbooks website here: https://pressbooks.pub/ancientgreek/chapter/4/.)

This means that Ancient Greek word order can shift without losing clarity, which allowed Ancient Greek speakers and writers — as well as translators — to emphasize different parts of a sentence by rearranging the words. For instance, putting the object at the beginning of a sentence would seem unusual in English — “Donuts, Leith eats.” — but is perfectly normal in Greek or if conversing with Yoda from Star Wars (LaFrance). But this also means that translating a Greek text (like, say, The Iliad for example) into English isn't as simple as finding a one-to-one match for English’s standard SVO word order. Instead, translators need to consider how word order is used to create emphasis or focus on certain ideas — which means translators often wind up rearranging a sentence’s structure significantly, depending on how they interpret not only what the author is saying, but how it’s being said.

Here's how this plays out in various translations of Homer’s epic poem, starting with Robert Fagles’s The Iliad, published in 1998. Fagles’s opening line reads:

“Rage—Goddess, sing the rage of Peleus’ son Achilles…”

Compare this to The Iliad: A New Translation by Caroline Alexander, from 2015:

“Wrath—sing, goddess, of the ruinous wrath of Peleus’ son Achilles…”

(It bears mentioning that Alexander was the first woman to translate The Iliad into English. Kudos, Caroline!)

Both Fagles and Alexander focus on the original Greek word μῆνιν, which loosely means “anger,” though in this instance refers to “a divine, superhuman kind of rage.” That’s according to translator Emily Wilson, writing for The Washington Post: “Only divinely backed ‘wrath’ could cause the level of destruction that Achilles brings about.” (If you haven’t read The Iliad, what follows is a lot of whacking, hacking, spearing, stabbing, and eye-gouging.) To emphasize Achilles’s fury, both Fagles and Alexander place the word right at the start of their opening passages and repeat it a second time. Yet, Fagles uses “rage” to describe Achilles' fury, while Alexander opts for “wrath.” “Rage” and “wrath” may seem interchangeable, but I contend that even these nuances can evoke different reactions.

Consider “rage.” It feels hot and immediate, whereas “wrath” smolders, feels more calculating, like something akin to revenge. “Wrath” is a noun, while “rage” is both a noun and a verb. When spoken, “rage” ends on that sharp “jah” sound. Physically, your vocal cords vibrate when you say it (Munro). On the other hand, the “th” at the end of “wrath” sounds like air being let out of a tire: “thhhhhh…” This is what's known as a voiceless dental fricative. Your vocal cords remain still (Stibbard). Maybe this doesn’t seem like an important consideration, but neurological research demonstrates that whether we’re reading a book silently or listening to its audio version our brains process words the same way (Deniz) — meaning, as writers, those “jah” and “th” sounds impact our readers.

But let’s return to Emily Wilson, the translator mentioned above, who also happens to be the first woman to translate both Homer’s The Odyssey and The Iliad in English, the latter published by W.W. Norton & Company in 2023. How did she handle the opening line?

“Goddess, sing of the cataclysmic wrath of great Achilles, son of Peleus…”

Wilson translates Achille’s fury as “cataclysmic wrath.” But she also chooses to lead with “goddess” over “rage” or “wrath” — which, personally, I love. Sure, she’s not foregrounding the poem’s central theme like Fagles and Alexander. But from the very first word, Wilson lays claim to this ancient text, subverting the historic exclusion of women from the Western classical canon. “If there were no Goddess,” she seems to be saying, “there would be no poem” — though this is my own interpretation.

Of course, unlike The Iliad, contemporary non-English novels usually receive a single translation — and tragically, less than one percent (0.7%) of these get translated into English at all (University of Rochester).

Contemporary Translations

One of the best examples I found demonstrating the translation process for contemporary non-English novels comes from Spanish-translator Sophie Hughes, who translated both Mexican writer Fernanda Melchor’s Hurricane Season and Chilean writer Alia Trabucco Zerán’s Clean. In an interactive New York Times piece entitled “The Art of Translation,” Hughes walks readers through her various drafts of translating one line from each novel. The choices she makes — swapping words, shifting structure, adjusting rhythm — all serve one purpose: to make the text feel “right.” It’s fascinating, watching translation happen firsthand. It also illustrates how, as writers, we can enrich our own word choices in subtle but powerful ways. You can visit Hughes’s piece here:

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2023/07/07/books/literature-translation.html

As far as the future of translation goes, attempts have already been made in handing over the reins of literary translation to artificial intelligence—though translators needn’t worry about finding themselves unemployed any time soon. According to Jeremy Klemin, writing for The Atlantic, these attempts have “only further cemented literary translation’s status as an indispensable art … The fact that [AI] remains woefully inadequate at literary translation — at least on its own — is a testament to the difficulty and value of the profession.”

On the other hand, translators themselves are embracing AI, actively experimenting with ways to integrate it into their craft (Pro Helvetica). But that’s a different essay for another time.

Summing Up

So, can reading translated works help me become a better writer?

In her book Why Translation Matters, notable literary translator Edith Grossman wrote, “Translation expands our ability to explore through literature the thoughts and feelings of people from another society or another time … [it] infuses a language with influences, alterations, and combinations that would not have been possible without the presence of translated foreign literary styles and perceptions … writers learn their craft from one another, just as painters and musicians do.”

Reading translated works does more than allow me, the reader, access to new stories. Each translation carries within it the echoes of a different culture, a different worldview, where word choices, tone, rhythm, and structure reflect not only the original author's voice but the translator’s artistry too. Through these layered interpretations, I, the writer, develop a better understanding of language’s malleability and potential beyond the limits of my mother tongue. As Gazelle Mba pointed out, language is never static — and in that flux, lies a wealth of creative possibility.

Saudade Revisited

And thus ends my essay and rounds of applause abound. But I’ve been working on this paper for weeks now and every time I reach this point, I feel like I’ve missed the mark. The more I write about translation, the more I realize I’m still struggling to articulate the essence, the particularity — the thing — that draws me to these novels. It’s not just their stories, or language, or styles. It’s deeper. Translations are never the original; they’re interpretations, reflections filtered through someone else’s eyes, which carries with it a sense of something ungrasped, of not being fully understood — a feeling I know too. In many ways, I’ve lived my entire life in translation — as an illegitimate child, a gay youth, a Jew, a trans woman, as someone with a disability, and more and more, as a person rendered invisible by age. There’s a parallel between the mismatch of author and translation, and the disparity between my inner self and the world’s perception of me — a yearning to be fully expressed, yet always falling short of complete understanding.

When I was sixteen, I was an exchange student in Rio de Janeiro. I never felt so alone. I left my small town in Virginia, believing I would arrive in Rio as a new person. I might even have friends. But I wound up ridiculed and bullied for my effeminacy there too — though the taunting felt sharper. I didn’t speak Portuguese. I had no language, no voice, to shield myself. Still, each day, my vocabulary grew. Then I encountered saudade.

When I asked a classmate to translate it, she said that was impossible — there was no English equivalent. Hearing this felt strangely comforting. I’d found a word as alien and inexpressible as the emotions then raging inside me. And maybe that’s why I’ve never forgotten that untranslatable word.

* * *

Some Sources, Poorly Cited

Aubrey, Mike. “A brief note on Greek word order.” Koine-Greek.com,

koine-greek.com/2023/08/18/a-brief-note-on-greek-word-order/.

Bell, Aubrey Fitz Gerald. In Portugal. Wentworth Press, 2016.

Deniz, Fatma, and Anwar O. Nunez-Elizalde, Alexander G. Huth and Jack L. Gallant. “The Representation of Semantic Information Across Human Cerebral Cortex During Listening Versus Reading Is Invariant to Stimulus Modality.” Journal of Neuroscience, 25 September 2019, 39 (39) 7722-7736; doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0675-19.2019.

Grossman, Edith. Why Translation Matters. Yale University Press, 2010.

Homer. The Iliad: A New Translation by Caroline Alexander. Translated by Caroline Alexander, Ecco, 2015.

Homer. The Iliad. Translated by Robert Fagles, Penguin Classics, 1998.

Homer. The Iliad. Translated by Emily Wilson, W. W. Norton & Company, 2023.

Hughes, Sophie. “The Art of Translation.” The New York Times, 7 July 2023, www.nytimes.com/interactive/2023/07/07/books/literature-translation.html.

Jordison, Sam. “Can Homer's Iliad speak across the centuries?” The Guardian, www.theguardian.com/books/booksblog/2016/feb/09/can-homers-iliad-speak-across-the-centuries.

Klemin, Jeremy. “The Last Frontier of Machine Translation.” The Atlantic, January 2024, www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2024/01/literary-translation-artificial-intelligence/677038/.

LaFrance, Adrienne. “An Unusual Way of Speaking, Yoda Has”, The Atlantic, December 2015, www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2015/12/hmmmmm/420798/.

Major, Wilfred E., and Michael Laughy. “Chapter 4. Parsing a Greek Verb.” Ancient Greek for Everyone. Pressbooks, pressbooks.pub/ancientgreek/chapter/4/.

Mechler, Cornelia. “Artificial intelligence in literary translation.” Pro Helvetica, prohelvetia.ch/en/whats-on/artificial-intelligence-in-literary-translation/.

Mba, Gazelle. “Spinning an illusion: what exactly do literary translators do?” The International Booker Prize, thebookerprizes.com/the-booker-library/features/spinning-an-illusion-what-exactly-do-literary-translators-do.

Munro, Colin. “The /ʤ/ sound.” English Language Club, 21 November 2014, youtu.be/vqL9ivPb09A?si=i_2wmwp1A1ZpXD3O.

Open University. “Discovering Ancient Greek and Latin, Section 10.4: Word order in Greek.” OpenLearn, www.open.edu/openlearn/history-the-arts/discovering-ancient-greek-and-latin/content-section-10.4.

Olsen, Lance. “Renewing the Difficult Imagination.” Shrapnel: Contemplations. Anti-Oedipus Press, 2024.

Paddock, Catharine. “Listening and reading evoke almost identical brain activity.” MedicalNewsToday, www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/326140.

Stibbard, Richard. “Consonants - The dental fricatives, /θ/ and /ð/.” Pronounce English Accurately - Dr Richard Stibbard, 13 February 2022, youtu.be/apRpjsCLGMg?si=C0Eg6M0ICMU1NkCy.

Wilson, Emily. “Emily Wilson on 5 crucial decisions she made in her ‘Iliad’ translation.” The Washington Post, 20 September 2023, www.washingtonpost.com/books/2023/09/20/emily-wilson-iliad-translation-terms/.

United Language Group. “Four Interesting Facts About Translation in Literature.” ULG's Language Services Blog, www.unitedlanguagegroup.com/learn/four-interesting-facts-about-translation-in-literature.

University of Rochester. “About.” Three Percent, www.rochester.edu/College/translation/threepercent/about/.

'In Translation' © 2024 Leith St. John